Blue Ventures has been implementing integrated health-environment programmes in Madagascar for more than a decade: combining family planning and other health services with local marine management and alternative coastal livelihood initiatives. So how did it feel when we placed these programmes under scrutiny?

The intersection of human emotions, organisational culture and scientific research is not often spoken about. But part of what made this research process so special and illuminating was those very dimensions. We set off with much excitement and some trepidation – delighted to finally be undertaking the study that we’d been dreaming about for years, yet unsure of what we might be about to uncover.

Diving deep

Previous research in the health-environment field has investigated whether integrated programmes generate better outcomes than single-sector interventions: does 1+1 = 3? Comparative studies such as this one conducted by the PATH Foundation in the Philippines are often held up as the gold standard.

More recently though, as organisations seek to refine and scale these programmes, our community of practice is diving deeper with a different set of questions. We’re no longer asking whether integrated programmes generate better outcomes, but rather how they do this: if the equation is indeed 1+1 = 3, what alchemy is at work here and how can we replicate it?

To take the plunge with these questions, we started by mapping out our key theories of change – established ways of thinking that are shared by many of our health-environment peers. We dubbed these “the goodwill effect”, “the fertility effect” and “the empowerment effect” – all pathways through which increasing access to family planning might contribute to more effective biodiversity conservation.

We then set about collecting a range of data – both quantitative and qualitative – in our longest-running Madagascar programme site so that we could map onto these theories of change to confirm or refute them.

Our integrated social survey – encompassing a variety of health, environment and livelihood indicators at the household and individual levels – was a thrilling first! It allowed us to analyse not only the outcomes of our different programmes but also the interactions between these outcomes (potential associations between different variables) – precisely where we believed the magic might be happening. The survey also included open-ended ‘most significant change’ questions which provided in-depth insights to complement the statistics.

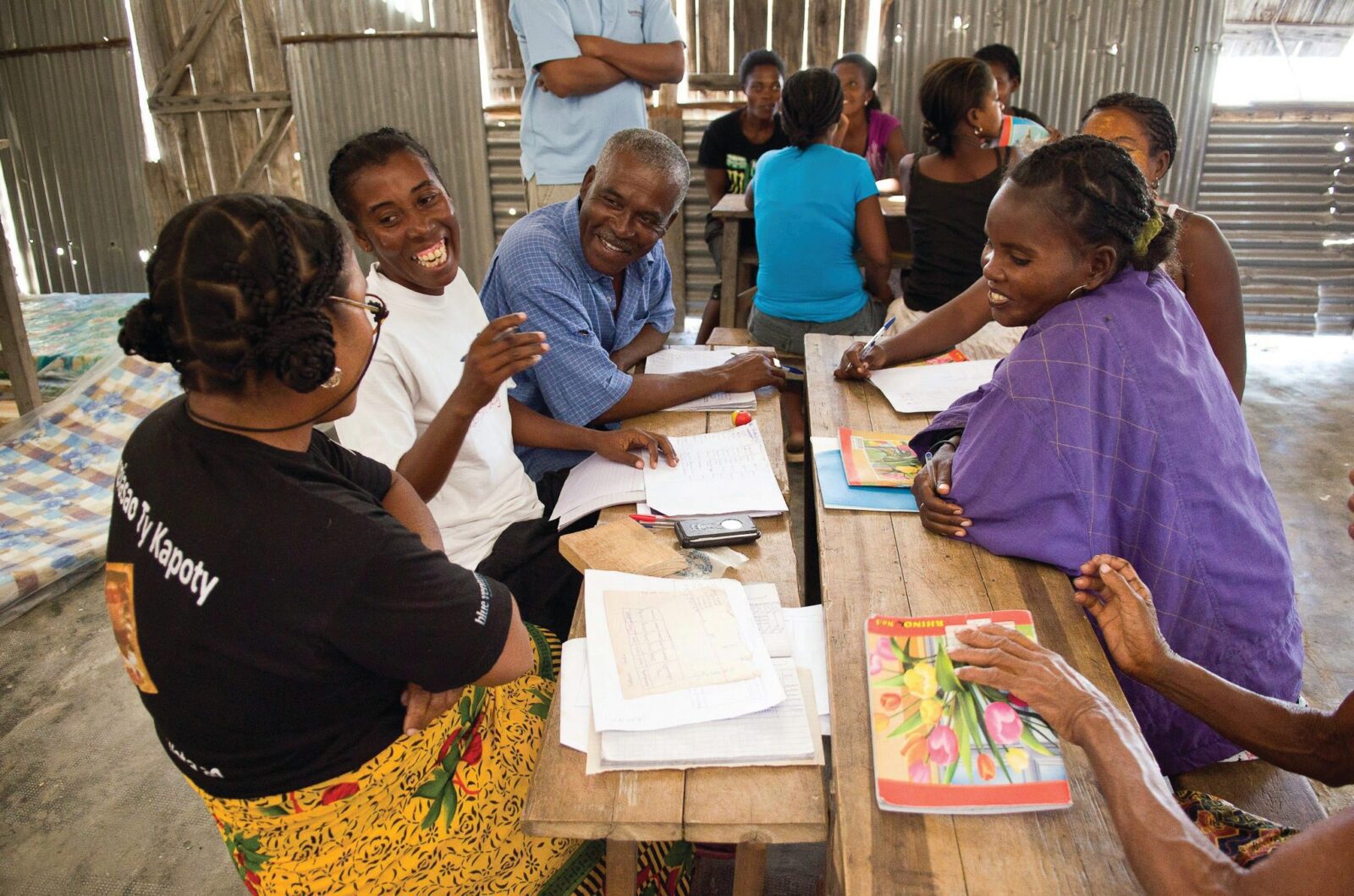

Photo: Brian Jones

Productive tension

The research process wasn’t all plain sailing. Assumptions were challenged, long-held beliefs were met with contradictory evidence, and big questions were raised. How did we weather these storms? Two key elements stand out: the push-pull dynamic within our team and the courage inherent in our organisational values.

The study was led by Rebecca Singleton, a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia who was also employed by Blue Ventures. At once an insider and an outsider, she brought a critical eye to the research and a strong commitment to holistic rights-based conservation work. Allied with our curiosity and a deep respect for our programmes, this kind of ‘oppositional collaboration’ proved to be extremely valuable. Together we were able to lean into difficult questions and surprising findings, pressing each other to let go of unfounded assumptions while remaining rooted in a belief in the value of this work.

Although different members of the team displayed varying levels of comfort with having their thinking challenged, ultimately we were all committed to deepening our understanding of our programming – whatever the revelations and results. A thirst for learning that’s hard-wired into Blue Ventures’ DNA trumped any attachment to established health-environment credos. Our organisational culture of openness and humility created a safe space for questioning, self-reflection and new thinking.

Arresting findings, critical questions

After months of cleaning and coding the data, the results were finally in! Family planning services were found to be highly valued by communities. Users reported experiencing better physical and mental health, being able to work and earn more, provide better for their children and focus on longer-term priorities such as better housing, savings and the future of fish stocks. Contraceptive uptake had more than doubled since we started supporting these services.

But some of our findings stopped us in our tracks. When family planning users in the Velondriake Locally Managed Marine Area said they appreciated being able to fish more with their free time, so that they could provide better for each of their children, we were alarmed. Could family planning be intensifying fishing activity and pressure on marine ecosystems – at least in the short term? Yet it also made intuitive sense. Of course people in this low-income context were working to raise their living standards even as they chose to space or limit their births.

This discovery raised some critical questions: Were we doing enough to support communities to secure food and income in ecologically sustainable ways? Should we be considering livelihood diversification as an essential third dimension in our health-environment work?

Other findings pushed us even further. Women who used family planning weren’t any more engaged in local resource management efforts than non-users. There was no magic empowerment pill here. And so we asked ourselves: What other initiatives might be needed to address restrictive gender norms? Tackling pressing healthcare priorities can certainly address one barrier to community engagement in marine conservation, but complementary initiatives that address other barriers are needed too.

Photo: Garth Cripps

Fresh insights, strengthened convictions

Letting go of established health-environment thinking has been a gradual process for our team – at once challenging and liberating. In its place we’ve been able to welcome in a more nuanced understanding of health-environment dynamics that’s allowing us to refine our own programming and technical advice to partner organisations.

Rather than trying to draw a direct line from family planning through to conservation outcomes, we’ve come to embrace a more messy reality. We see that improved healthcare must be set alongside livelihood diversification, gender equality and local management initiatives in order to advance conservation. Family planning is not a panacea, but it is highly valued by communities and can open the door to new opportunities for engagement.

Our research, presented in full here, has further affirmed our rights-based commitment to this holistic way of working. The healthcare support that we provide clearly isn’t predicated on any expectation of immediate conservation benefits. It’s part of a wider constellation of human rights – to reproductive choice, health, food, decent work, education, property tenure and much more – that must be respected and upheld for communities to be able to manage their fisheries sustainably.

We share our experiences here as an invitation to our peers to dig into their own health-environment programmes and assumptions with courage, openness and humility. You may hit some rocks at first – uncovering gaps and potential unintended consequences – but beyond that there’s treasure to be found! We’re moving forward with a deeper understanding of the interconnected challenges faced by our partner communities and a more holistic approach than ever.

Conservation, contraception and controversy: Supporting human rights to enable sustainable fisheries in Madagascar has just been published in Global Environmental Change

Visit this interactive webpage for an overview of the key findings

Learn more about how Blue Ventures’ integrated health-environment programming has lead to contraceptive uptake in Velondriake